V8s, fat bank accounts, and insecurity are trademarks of South Sudan peace

By Ruot George

The V8s roar on the streets of South Sudan’s capital Juba, and bank accounts of elites swell-these have been the rewards for rebellion, and talking their ways into a combined transitional government.

The country however continues to bleed with insistent insecurity-intercommunal violence caused by cattle raids and counter raids and revenge attacks.

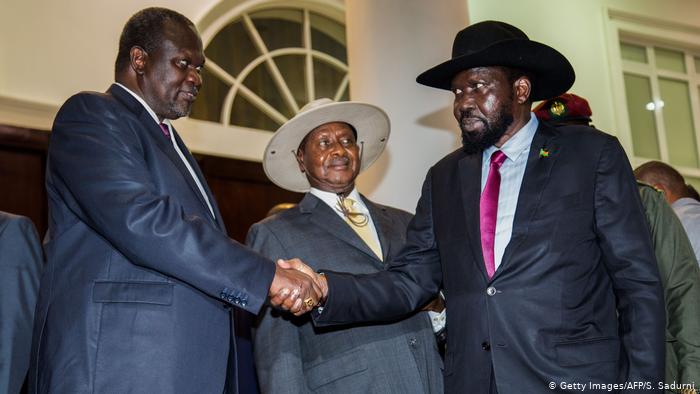

Three years ago, several rebel groups including the SPLM-IO led by First Vice President Riek Machar reached a deal with President Salva Kiir’s administration to form a transitional arrangement that would pacify the country and lead it into democratic elections.

While the leaders insist the deal is being implemented well, analysts believe the deal is dead stuck.

“We are lagging terribly behind, three years have finished and we are still struggling to form the government and put the structures in place, nothing has moved beyond that,” James Okuk, a political analysts and professor at the University of Juba said.

“So far we are even stuck in the constitution making which is the condition for elections and three years have gone and the period is only 36 months and already if three years have gone we are remaining with six months, I don’t think we can achieve what remains in six months,” he said in a talkshow on the UN’s Radio Miraya.

“People holding importance positions in the peace agreement have changed, they have many V8s and their lifestyles have changed, and their bank accounts in the banks are fat.”

Signed in September 2018, the pact was billed as the only sensible way of ending six years of crisis in South Sudan.

The crisis left 400,000 people dead, displaced four million others and led to economic chaos by reducing crude oil production, the country’s main revenue source.

While the parliament has been instituted and state governments formed, the security arrangement that forms the basis of the country’s future profession army has not yet been done.

A hybrid court for transitional justice in South Sudan, prerequisite of the deal has also not been instituted.

Joseph Maker Machiek, a law student at the University of Juba warned it would be difficult to hold elections when the transitional period ends, blaming rampant insecurity across the country.

“I see now three years and nothing has changed, insecurity on the highways, so I can’t expect a free and transparent elections,” Machiek told Juba Echo in an interview.

“Elections cannot be held peacefully when there is no meaningful peace among the communities,” he said.

Like him, Awiel Aduot Lual said the pact has not reflected in security for the communities in the country.

“I want to say there is need for peace for us to move freely to our home states,” Lual said.

“Nothing is possible in the current situation.”