By: David Y. Deng.

The question of the size of political representation in a democracy is a persisting one. Some countries have voted for reforms to reduce the size of legislature and others are considering the need for reduction. The issue of optimal size of political representation continues to be a complex policy issue that cannot be ignored. For South Sudan which acrimoniously passed its amended National Elections Act in September 2023 this important issue and that of geographical constituencies seats allocation were given little or no attention. The Amendment Act, passed in anticipation of the upcoming 2024 general elections, proposed the size of legislature to be 332 members distributed as follows; 50% geographical constituencies representation, 35% women representation, 15% party list representation, and 5% to be appointed by the elected president. The controversial issue of 5% representational appointment by the president aside (well discussed in Sudd Institute Review Issue), the two central questions that I will examine in this piece are; 1)whether this proposed level of political representation is economically efficient for a country already struggling with the worst humanitarian crisis, dire macroeconomic instability, and poor productivity and 2)on the modality to be adopted for the distribution of proposed additional geographical constituencies in absence of updated census data.

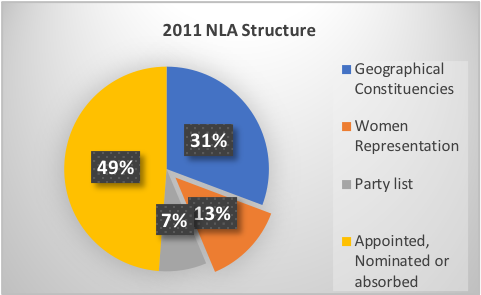

On the question of size, let me provide a brief background to the numbers. The current size of 332 legislative representation specified by the amendment Act 2023 to Elections Act 2012 is not a totally new number. The proposed membership is the same in size as the first constituted South Sudan National Legislative Assembly (SSNLA) in 2011 just after independence. However, the structure of representation is what might have been different. The National Legislative Assembly as convened by Presidential Decree No. 10/2011 of August 2011 comprised 170 former elected members of Southern Sudan Legislative Assembly (SSLA), 96 former members of Sudan National Assembly who were absorbed after separation, and 66 members that were appointed by the president. These numbers add up to the currently proposed size of 332 and if the 100 membership of the Council of States is included, the combined total size of South Sudan Legislature for both houses come to 432.

Does this mean the Amendment Act did not increase the size of political representation as of 2011 and there is no need to worry about the bloated parliament? The answer may be yes if we look at the numbers at glance. However, looking at the numbers critically, the first convened legislature was meant to be accommodative in nature and close to 50% of its membership was either nominated, appointed, or absorbed. There was no clear policy justification for absorption of 96 members of parliament from then Sudan National Assembly and the appointment of nearly 20% of the NLA by the president other than to accommodate some members. And so, the current Amendment Act just formally legalized the previous accommodative share of TNLA, but again with no clear policy objectives and goals on improving democratic representation.

Back to the size of political representation, the core objective had always been to try to balance the cost of running the legislature and ensuring adequate democratic representation. If there were to be no cost implications of maintaining the size of legislature and assuming other factors remains constant, the ideal situation would be to have a bigger representation to ensure adequate democratic outcomes. However, that is not always the case.

Although there is no clear rule of thumb when it comes to determining the optimal size of political representation, the cost of running the legislature remain the main determining factor when examining the issue of the size of legislature. The cost estimates outlined on the chart above are just the modest expenses for paying members of the legislature salaries and allowances for selected East African Countries in comparison to South Sudan. The chart does not capture other significant costs of running the legislature.

Although the MP take home salary and allowances in South Sudan is relatively low compared to other East African countries, the total cost of running the proposed size of political representation is significantly large relative to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). There is limited data on the actual gross salary including allowances for a South Sudanese MP, but just most recently, South Sudan MPs raised their salaries to nearly 2,000 USD per month amidst some outcry from citizens. Besides this amount there are also undisclosed hefty allowances that MPs enjoy. From reports obtained from conversations with individuals familiar with this issue, South Sudan MPs are believed to have received 3 installments of around 15,000 USD each for medical allowances plus 50,000 USD each as vehicle allowances in the last one year. The modest rough estimate for the purposes of this analysis would put an MP’s gross earning including allowances to nearly 6,000 USD per month which translates to annual legislature renumeration cost of about 31 million USD. This is economically draining for a country that generate a meagre annual economic output of 6.7 Billion3 in (GDP in USD), making it one of the poorest in the world. This cost is much closer to countries such as Tanzania that generate an annual economic output of about 45 billion USD in GDP, or nearly 10 times that of South Sudan. With South Sudan finding it even hard to meet the basic functions of the state and with over three quarters of the country’s population reported to need humanitarian assistance in 20244, the economic cost of funding the bloated legislature is unreasonable and unjustified.

Furthermore, the ratio of population to representation is quiet low in comparison to many countries and may also not justify this bloated legislature (assuming that the quantity of political representation per se were to guarantee the quality of democracy). After all, South Sudan has experimented with one of the largest legislatures (550 members appointed to the current parliament as per ARCISS) in East Africa and by general observation from this experience, the quality of democratic representation under the currently bloated parliament has, arguably, been substandard in terms of policy formulation and general development.

On the issue of allocation of 50% (166 Seats) to geographical constituencies, it is important to note that the number of geographical constituencies as of 2010 elections were 102. This means there will be about 64 additional seats to be allocated. Constitutionally, the mandate to review and recommend more geographical constituencies is supposed to be undertaken by the National Elections Commission (NEC) in line with the results of the census that should be conducted every ten (10) years. The guidelines on seats distribution are spelled out in well-defined formula in the Elections Act. The 102 geographical constituencies were based on 2008 census data. Due to well-known challenges of conflict, funds, and widespread displacement, the conduct of national census as stipulated in the constitution of South Sudan has never been feasible. This raises the question of the allocation of additional constituencies created by the Elections Amendment Act. The question of who gets what? How? and why? that will be adopted by NEC to ensure equitable and justifiable share will a daunting one that could create more conflict. In the absence of the most objective census data, there is chance for arbitrariness. It should also be noted that there is a possibility that the population of South Sudan has either stagnated or declined as of the last national census in 2008 and with no clear population data, the Elections Amendment Act has no policy justification for the increase of geographical constituencies.

In conclusion, the proposed size of South Sudan legislature is bloated and may not be adequately supported from economic efficiency angle and due to lack of clear census data that could inform the allocation of new geographical constituencies that may results in arbitrary distribution that could create conflict.

Recommendations:

- From economic efficiency point of view, it is recommendable to reconsider the size of recently proposed legislature to reduce the cost for the country’s economy that is already ailing.

- It is recommendable to retain the previous number of constituencies created from 2008 census data with only slight incremental modal on women representation and other marginalized groups and caping the total size at 200. Any new additions to geographical constituencies should wait until the next census cycle.

- All new genuine additions (those increments considered by point 2 of this recommendation) to the size of legislature should be reviewed and recommended by NEC to the parliament. The parliament might have overstepped its constitutional mandate in the recently passed amendment as NEC was sidestepped in the process.